Architecture Undone

The following article titled ‘Architecture Done’ by Dr Mick Wilson was published in Beyond Pebbledash 2014.

Dr Mick Wilson is Head of Department in the Faculty of Applied & Performing Arts at the Valand Academy, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. He studied at the National College of Art & Design, Dublin (1986-90), and has a PhD from NCAD/NUI (2006). Throughout the 1990s he worked as an artist and also taught on several programmes in cultural studies, history of technology, art theory, art history and contemporary art practice at art schools and universities in Ireland.

Pebbledash (also known as ‘roughcast’) is a coarse surface used on outside walls consisting of lime, sometimes cement, mixed with sand, small gravel, and/or pebbles, or even shells on occasion. The materials are combined to form pliable slurry, which is then thrown at the working surface with a trowel. The skill is to achieve an even distribution of the material without lumps, ridges or runs, and without any of the underlying surface being revealed. There is a distinction made in the trade between roughcasting (incorporating the stones directly into the material slung carefully at the surfaces to be covered) and pebbledashing (adding the stones on top of the immediately prepared surface).

The slum clearance and ambitious social-housing schemes of the mid 20th century created large stretches of pebbledash suburbs in Dublin. The spread of the city beyond the canals in new labyrinthine housing schemes in Ballyfermot, Crumlin and Finglas created a particular urban landscape of garden cities, with the ubiquitous pebble-dashed surfaces – solid public hopes for a better life than that on offer in the notorious tenements of the inner city.

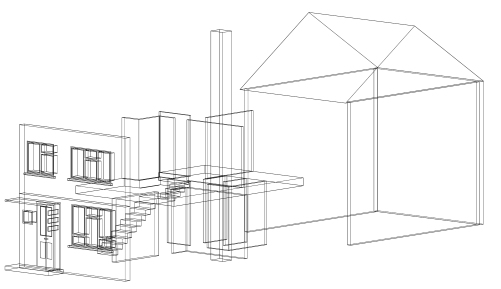

For the project BEYOND PEBBLEDASH, an expanded installation-cum-discursive platform, Paul Kearns and Motti Ruimy have erected in Clarke Square at Collins Barracks (home of the National Museum of Ireland’s Decorative Arts & History collection) a simulacrum of one of these ‘typical’ Dublin local authority pebble-dash houses (scale 1:1) incorporating a pebbledash façade and metal frame skeletal body. This artwork is a provocation to critical reflection and public dialogue, building upon the artists’ earlier research project REDRAWING DUBLIN, and responding to the deficit in public debates on housing in Ireland. They propose that we can move past a reductive and under-analysed rhetoric of ‘property bubbles’, ‘ghost estates’, ‘reckless lending’ and ‘rogue developers’ to address the question of contemporary urbanism as a fundamental dimension of our cultural and social imaginaries.

While, for the artists, Ballyfermot is the exemplary instance of the mid-20th century Dublin social housing expansion, for this writer, Crumlin is the most familiar example, having grown up there in an end-of-terrace house (the end-of-terrace house being much coveted for the side entrance to the back garden, enabling a multiplicity of domestic possibilities that mid-terrace dwellers could only speculate upon). Mostly designed in the 1930s, but built over several decades, this basic house unit has been described as having ‘an almost classical elegance’ and as being ‘quite modernist in style: streamlined, clean-cut lines, stripped of virtually any decoration, with the aesthetic relying on the bold structure of the buildings, the paint colour used, and the simplest of render detail in the form of a distinctive band running across the middle of every house, and around doors and windows.’1 While known prosaically as the ‘two-up-two-down’, there are several variants within this typology, including three-bed- room versions. One persistent feature of these was the ubiquitous pebbledashed surface, an external insulator, a decorative mask and a unifying surface treatment that has often been reworked in subsequent generations to break the integrated surface with the assertion of individual propertied identities. It is now very familiar to see the even-tempered pebbledashed surfaces of the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s displaced by various forms of blacklined ‘heritage’ stone facing and faux granite and sandstone surface treatments of later decades. While some may baulk at these ersatz interruptions of the once integrated surface, there is of course something terrifically social and anti-architectural in the refusal of ‘an almost classical (quite modernist) elegance’ by the punkish faux grandeur, one-upmanship and longing for visible ‘home’ signalled by these redressed surfaces.

In discussion with the artists, they identify their intentions in constructing a 1:1 literal three-dimensional drawing of this classic house type with the desire to examine a range of themes that include the delimitation of architectural practice, the status of the ‘model’ within architectural practice and the transitioning back and forward between moments of representation and moments of construction in architecture, and the rethinking of the life cycle of architecture by attending to the phase of ‘post-construction’ that potentially rewrites earlier moments in the architectural process.

These themes are elaborated by the artists through a series of questions: What is architecture? Where does it begin and end? Is it in the line drawing, the blueprint itself? Is it where the architect conceptualises and expresses ideas, or is it in the manifestation of the three-dimensional structure which people inhabit? Given that architecture modelling is usually employed to illustrate an idea or concept of a build- ing, normally at a smaller scale to facilitate probing the concept of the building in a simulated environment, what happens when one reverses this movement and constructs a 1:1 model after the fact of the building’s construction? In what way might this reversal and rescaling of the ‘model’ allow one to probe the wider conceptions of the built environment and the professional ‘habitus’ of those who generate habitats?

While ‘architecture’ is usually processed in a linear form – i.e. concept, drawing, construction, inhabitable space – the BEYOND PEBBLEDASH installation is a stage in ‘architecture’ that deals with ‘post-construction’. In expli- cating ‘post-construction’, the artists reference the work of Rachel Whiteread, Bruce Nauman, Dan Graham, Gordon Matta-Clark and Christo, among others, and the response to a particular building after it has being built and inhabited. The artists wish to ask to what degree can the meanings and the overarching narratives of the particular building examined be contested and reordered by this post-construction intervention? Furthermore, the artists wish to insert this 1:1 model, referencing an earlier moment of urban expansion in Dublin, as a contribution to the current debate on urban futures and the address to spatial legacies of the boom years.

In this way, BEYOND PEBBLEDASH is not simply a matter of surfaces or the reclamation of urban imaginaries obscured by the accumulation of historical layers of the abandonments of city life by the managers of the city. It is a raised discursive volume, a clamouring frame, asserting the demand for public debate on urban futures, a demand for more criti- cal analysis of the recent past, and a refusal of the closure of potentials in our multi-urban (urban, ex-urban, sub-urban, extra-urban…) futures.

In one register, this work continues a tradition of art- works that extemporise on the ur form of the house, with precedents in Michael Landy’s Semi-detached (2004), Rachel Whiteread’s House (1993), Gregor Schneider’s Death Haus U R (since 1985) and Gordon Matta-Clark’s Splitting (1974). In a way similar to Landy’s and Whiteread’s projects, BEYOND PEBBLEDASH, looks at the public meaning of domesticity and the nature of social being through simulacral architec- tural form and displacements of form.2 The work also con- nects to a North American tradition of conceptual art and architectural critique, as in the work of Matta-Clark and others such as Dan Graham.

There is, of course, a persistent dialogue between art and architecture, whereby both insulated practices often speak past each other to declaim the blurring of their respective boundaries. The restatement of the house form, the restaging of the scenography of the house, is perhaps a symptomatic trope of this dialogue. However, it is notable that in this instance the artists have a very particular reading of the 1:1 ratio model house as a kind of architectural practice in reverse. The artists note that the architectural process usually starts with a concept that is expressed in a line drawing and ends with the erection of the building itself. With BEYOND PEBBLEDASH, the process in contrasts starts with an exist- ing building, an actually existing house No. 5 Loch Conn Drive, Ballyfermot and finishes with the 3D line and façade installation. The result is uninhabitable except in some imaginary projection of life; one moves into this house by metaphorical transports and takes up residence in the con- tested site of our urban imaginaries. This is architecture un- done so as to do constructive work on architecture.

There is another tradition of art practice oriented by the form of the house and by the substantive questions of urban housing and planning practices, among which, Jeanne Van Heeswijk’s Het Blauwe Huis (The Blue House, 2005-10) is an exemplary moment.3 Van Heeswijk’s project was to create a space for the unplanned in an urban extension of Amsterdam IJburg through an artwork that created a ‘residents association of the mind’ in a private house, challenging the domination of space by the master-planners of a new urban area. Within this tradition, the house becomes a vol- ume through which discursive production and all manner of social practices are mobilised in the attempt to catalyse a space for the unplanned within an oppressively overdetermined master-planned urban landscape. While Ireland’s spatial catastrophe may be described in many hyperbolic terms, the Dutch artist’s analytics of over planning and the repression of spaces of the unplanned do not seem appropriate in the Irish case. However, the need for a space of radical ques- tioning and of public debate is, of course, evident in both these contexts.

In the most privatised of urban spaces (Dublin is a peculiarly ‘owned’ city with a dearth of authentically public space hidden by the faux public zones of shopping precincts and cultural quarters), we desperately need spaces of public dialogue. In a way that is different, but cognate, with Het Blauwe Huis, BEYOND PEBBLEDASH seeks to activate an agonistic public sphere where there will be a contestation of meaning, value, purpose and questions of the public good. The discursive space engendered by the artwork is a central dimension of these art practices, something that moves the work far beyond the sometimes rarefied terms of art criticism into questions of everyday living and our wish for participation in the remaking and reclaiming of our cities.

Of course, this talk of ‘our’ cities and this collective ‘we’ that is invoked by the artists in framing their project is not unproblematic. It is recognised as precisely the problem of who will be constituted as the owners of the city’s future, and who can claim the right to speak of the city, for the city, and through the city. The artists here have secured a path to the public hearing their claims and counterclaims using the public space of the museum to foment a debate. The question is open as to whether the conversation that they are construct- ing will open out beyond mere repetitions of the well-worn rhetorical formulae that pebbledash over the cracked surfaces of our public life, or whether they can throw some well- judged stones, inserting some gritty resistances, into the thick slurry of contemporary Irish journalism and political commentary.

The artists have designed an edifice for discourse. It needs others to come and inhabit this house and give to it the form of life by taking possession once more of a paradigm of public architecture. Move into this house. Extend this house. Redraw this house. Resettle this house. Reanimate this house. Call this house to order and open into urgent debate the contest for the public good and the commonweal against unbridled and unthinking private interests.

–––––

Dr Mick Wilson is Head of Department in the Faculty of Applied & Performing Arts at the Valand Academy, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. He studied at the National College of Art & Design, Dublin (1986-90), and has a PhD from NCAD/NUI (2006). Throughout the 1990s he worked as an artist and also taught on several programmes in cultural studies, history of technology, art theory, art history and contemporary art practice at art schools and universities in Ireland.